Quddus (Mendelson) - Jerusalem (Mendelssohn)

Quddus yoki diniy kuch va yahudiylik to'g'risida (Nemis: Quddus oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum) tomonidan yozilgan kitobdir Musa Mendelson birinchi marta 1783 yilda nashr etilgan - o'sha yili, Prussiya zobiti bo'lganida Christian Wilhelm von Dohm Mémoire-ning ikkinchi qismini nashr etdi Yahudiylarning fuqarolik holatining yaxshilanishi to'g'risida.[1] Musa Mendelson yahudiy ma'rifatining muhim shaxslaridan biri edi (Xaskalah ) va uning ijtimoiy shartnoma va siyosiy nazariya bilan bog'liq falsafiy traktati (ayniqsa, savolga tegishli) din va davlat o'rtasidagi ajratish ), uning qo'shgan eng muhim hissasi deb hisoblash mumkin Xaskalah. Arafasida Prussiyada yozilgan kitob Frantsiya inqilobi, ikki qismdan iborat bo'lib, ularning har biri alohida-alohida varaqlangan. Birinchi qismda siyosiy din nazariyasida "diniy kuch" va vijdon erkinligi muhokama qilinadi (Baruch Spinoza, Jon Lokk, Tomas Xobbs ) va ikkinchi qism Mendelsonning shaxsiy kontseptsiyasini muhokama qiladi Yahudiylik ma'rifatli davlat tarkibidagi har qanday dinning yangi dunyoviy roli to'g'risida. Musa Mendelson o'z nashrida yahudiy aholisini jamoatchilik ayblovlaridan himoya qilishni Prussiya monarxiyasining hozirgi sharoitini zamonaviy tanqid qilish bilan birlashtirdi.

Tarixiy ma'lumot

1763 yilda ba'zi ilohiyot talabalari tashrif buyurishdi Musa Mendelson sifatida uning obro'si tufayli Berlinda xat yozuvchi va ular Mendelsonning nasroniylik haqidagi fikrini bilmoqchi ekanliklarini ta'kidladilar. Uch yildan keyin ulardan biri shveytsariyalik Johann Caspar Lavater, unga o'zining nemis tilidagi tarjimasini yubordi Charlz Bonnet "s Palingénésie falsafasi, Mendelsonga jamoat bag'ishlovi bilan. Ushbu bag'ishlovda u Mendelsonni Bonnetning sabablarini xristianlikni qabul qilish yoki Bonnetning dalillarini rad etish to'g'risida qaror qabul qilishni talab qildi. Juda shuhratparast ruhoniy Lavater o'zining Mendelson va Mendelsonning javobiga bag'ishlanishini 1774 yilga tegishli bo'lgan boshqa maktublar bilan birga nashr etdi, shu jumladan doktor Mende Kolselening "Mendelson munozarasi natijasida ikki isroilni suvga cho'mdirgan" ibodati. U Mendelsonning obro'sini va diniy bag'rikenglik haqidagi maktublarini suiiste'mol qildi, o'zini zamonaviy yahudiylikning o'ziga xos nasroniy Masihiga aylantirdi, Xaskalah nasroniylikni qabul qilish sifatida.[2]

Ushbu fitna, allegorik dramada O'rta asrlarning salib yurishlari davriga ko'chirildi Natan der Vayz Mendelsonning do'sti Gottxold Efrayim Lessing: Lessing yosh ruhoniy Lavaterni tarixiy shaxs bilan almashtirdi Saladin zamonaviy ma'rifatli tarixshunoslik nuqtai nazaridan salib yurishlarining bag'rikenglik qahramoni sifatida namoyon bo'ldi. Bilan javob bergan Natanning maqsadi halqa masal, olingan Bokkachio "Dekameron "va Lessing o'z dramasini Musa Mendelsonga bag'ishlangan bag'rikenglik va ma'rifat yodgorligi sifatida yaratmoqchi edi. Lessing ochiq fikrli va zamonaviy mason tipi bo'lgan va o'zi ham jamoatshunoslik bahsiga sabab bo'lgan (Fragmentenstreit ) ning tarixiy haqiqati haqida Yangi Ahd pravoslav lyuteran Hauptpastor bilan Johann Melchior Goeze 70-yillarda Gamburgda. Nihoyat unga 1778 yilda Herzog Brunsvik tomonidan taqiq qo'yilgan. Lessingning ma'lum bir din asoslari to'g'risida so'rash va uning diniy bag'rikenglik borasidagi sa'y-harakatlarini ko'rib chiqishning yangi usuli hozirgi siyosiy amaliyotning aksi sifatida nazarda tutilgan edi.

1782 yilda "Toleranzpatent" deb nomlangan deklaratsiyadan so'ng Xabsburg monarxiyasi ostida Jozef II va "lettres patentlari" ni amalga oshirish Frantsuz monarxiyasi ostida Lyudovik XVI, din va ayniqsa Yahudiylarning ozodligi Elzas-Lotaringiyada shaxsiy munozaralarning sevimli mavzusiga aylandi va bu munozaralar ko'pincha xristian ruhoniylari va Abbeslarning nashrlari bilan davom etdi.[3] Mendelsonning Quddus yoki diniy kuch va yahudiylik to'g'risida uning bahsga qo'shgan hissasi sifatida qaralishi mumkin.

1770-yillarda Mendelsondan tez-tez Shveytsariya va Elzasdagi yahudiylar vositachilik qilishni so'rashgan - va bir marta Lavater Mendelsonning aralashuvini qo'llab-quvvatladi. Taxminan 1780 yilda Elzasda yana bir antisemitik fitna bo'lib o'tdi, o'shanda Fransua Do'zax yahudiy aholisini dehqonlarni charchatishda aybladi. Zamonaviy Alsatiy yahudiylarida er sotib olish uchun hech qanday ruxsat yo'q edi, lekin ular ko'pincha qishloq joylarida uy egalari va qarzdorlar sifatida mavjud edilar.[4] Musa Mendelsondan Altsat yahudiylarining jamoat rahbari Herz Cerfberr tomonidan reaksiya ko'rsatishni so'ragan. Memira yahudiy aholisini qonuniy kamsitish haqida, chunki bu Prussiya ma'muriyatining odatiy amaliyoti edi. Muso Mendelson uyushtirgan a Memira Prussiya zobiti va mason Christian Wilhelm von Dohm bunda ikkala muallif ham yoritilmagan holatni tasdiqlashni fuqarolik holatini umuman yaxshilash talablari bilan bog'lashga urindi.[5]

Bu borada Muso Mendelson o'z kitobida isbotlagan Quddus o'sha yili nashr etilgan, yahudiylarning fuqarolik holatining "yaxshilanishi" ni umuman Prussiya monarxiyasini modernizatsiya qilishning dolzarb ehtiyojidan ajratib bo'lmaydi. Buning sababi, nima uchun Muso Mendelson eng taniqli faylasuflardan biri sifatida Xaskalah edi Prussiya, bu erda yahudiylarning ozodligi holati qo'shni mamlakatlar bilan taqqoslaganda eng past darajada ekanligi bilan tushunilishi kerak. Xullas, yahudiy aholisi 19-asrda boshqa mamlakatlarga qaraganda ko'proq singib ketishga majbur bo'lgan: Xogenzollern monarxiyasi o'zlarining farmonlari bilan ergashganlar. Xabsburg monarxiyasi - 10 yil kechikish bilan. 1784 yilda, Mendelsonning kitobi nashr etilganidan bir yil o'tgach Quddus, Xabsburg monarxiyasi ma'muriyati rabbonlarning yurisdiksiyasini taqiqladi va yahudiy aholisini o'z yurisdiktsiyasiga topshirdi, ammo past huquqiy maqomga ega edi.[6] Monarxiyaning ushbu birinchi qadami murosasizlik tomon yo'naltirilgan bo'lishi kerak edi. 1791 yilda Milliy Majlis Frantsiya inqilobi ning yahudiy aholisi uchun to'liq fuqarolik huquqlarini e'lon qildi Frantsiya Respublikasi (Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen ).

Musa Mendelsonning "Diniy kuch to'g'risida" risolasi va uning tarkibi

Musa Mendelson yoshligidanoq klassik ellin va rim faylasuflari va shoirlarining nemis tiliga tarjimasiga katta kuch sarflagan yuqori ma'lumotli olim va o'qituvchi edi va u juda mashhur va ta'sirchan faylasufga aylandi. Xaskalah. Uning kitobi Quddus oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum yahudiy ma'rifatining asosiy asarlaridan biri sifatida qaralishi mumkin.

Dohmni himoya qilishda haqiqiy "melioratsiya" mavzusini tushuntirib beradigan ushbu matn falsafaga qo'shgan hissasi sifatida hali ham kam baholanadi - ehtimol bu muallifning tarixiy holati va ijtimoiy sharoitlari bilan bevosita bog'liq edi. Boshqa tomondan, Xaskaladan xavotirga tushgan ko'plab tarixchilar Musa Mendelson haqidagi qahramonlik obrazini tanqid qildilar, u XVIII asr boshlarida yahudiy ma'rifatining boshlang'ich nuqtasi sifatida namoyon bo'ldi.

Yahudiylikning hozirgi ahvoliga nisbatan O'rta asrlarning o'rnini egallagan zamonaviy nasroniy xurofotiga oid ayblovlar va shikoyatlar haqida (favvoralarni zaharlash, nasroniy bolalarni Pessada marosimlarda qirg'in qilish va hk).[7] uning melioratsiya mavzusi din va ayniqsa davlatdan ajratilishi kerak bo'lgan din edi.

Kitoblarining ikki qismidan tashqari unvonlari yo'q Erster va Zweiter Abschnitt ("birinchi" va "ikkinchi bo'lim"), va birinchisi davlatning zamonaviy ziddiyatlarini, ikkinchisi dinning ziddiyatlarini aniq ko'rib chiqdilar. Birinchisida muallif o'zining siyosiy nazariyasini adolatli va bag'rikeng demokratiyaning utopiyasiga qarab ishlab chiqdi va uni Muso Qonunining siyosiy urinishi bilan aniqladi: shuning uchun "Quddus" unvoni. Ikkinchi qismda u har bir din xususiy sektorda bajarishi kerak bo'lgan yangi pedagogik ayblovni ishlab chiqdi. Bu unga qisqartirildi, chunki bag'rikeng davlat har qanday dindan ajralib turishi kerak. Shuning uchun Mozaika qonuni an'anaviy yurisdiktsiya amaliyoti, agar tolerant davlat bo'lsa, endi yahudiylikning ishi emas edi. Buning o'rniga dinning yangi ayblovi odil va bag'rikeng fuqarolarni tarbiyalash bo'ladi. Butun kitobda Prussiya monarxiyasining zamonaviy sharoitlari va turli dinlarning huquqiy maqomi to'g'risida Muso Mendelsonning tanqidchisi sarhisob qiladi, bu nihoyat uning aholisining e'tiqodiga ko'ra fuqarolik holatini anglatadi - Christian Wilhelm von Dohm "s Memira.

Falsafiy masala (birinchi qism)

Mendelsonning siyosiy nazariya kontseptsiyasini Prussiya monarxiyasidagi tarixiy vaziyatdan anglash kerak va u o'z nazariyasini Kantgacha shakllantirgan. 1771 yilda u ham tanlangan Yoxann Georg Sulzer, uni falsafiy bo'limning a'zosi bo'lishini xohlagan Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Ammo Sulzerning chaqiruvi tomonidan taqiqlangan Buyuk Frederik. Qirollik aralashuvi din va davlatning ajratilishi masalasida Prussiya monarxiyasi tarkibidagi ma'rifat va bag'rikenglik chegaralarini aniq ko'rsatib berdi.[8]

1792 yilda Immanel Kant ichida ishlatilgan Die Ginalzen der Gernzen der gullab-yashnaydi Vernunft ning pastligi haqidagi an'anaviy diniy dalil Mozaika qonuni bu insoniyatni zo'ravonlik bilan axloqiy munosabatlarga majbur qiladi, shuning uchun uni din deb tushunish mumkin emas edi.

Despotizm (Spinoza va Monteske)

Musa Mendelson 1783 yilda nashr etilgan risolasining birinchi qismini dinni juda o'xshash tushunchasi bilan ochdi, ammo u siyosiy misol sifatida "Rim katolik despotizmi" ni tanladi. Garchi uning davlat va din o'rtasidagi ziddiyatni aql va din o'rtasidagi ziddiyat deb ta'riflashi, bu bilan juda yaqin bo'lgan Baruch Spinoza uning ichida Tractatus theologico-politicusMendelssohn Spinozani qisqacha eslatib o'tdi,[9] unga mos keladigan metafizikadagi xizmatlarini taqqoslash orqali Xobbs 'axloq falsafasi sohasida. Monteske So'nggi siyosiy nazariya zamonaviy vaziyat o'zgarganligini ta'kidladi, bu mojaro nihoyat cherkovning tanazzulga uchrashiga olib keldi, shuningdek, kutilgan oxiridan umid va qo'rquv paydo bo'ldi. qadimiy rejim:

Der Despotismus shap den Vorzug, daß er bündig ist. Shunday qilib, Forderungen dem gesunden Menschenverstande sind, shuning uchun sind sie doch unter sich zusammenhängend und systematisch. […] Shunday qilib, Verfassung kirchliche vafot etgan Grundsätzen auch nach römisch-katholischen Grundsätzen. […] Räumet ihr alle ihre Forderungen ein; shuning uchun wisset ihr wenigstens, woran ihr euch zu halten habet. Euer Gebäude ist aufgeführt, und in allen Theilen desselben herrscht vollkommene Ruhe. Freylich nur jene fürchterliche Ruhe, Montesquieu sagt, vafot etadi Abends in einer Festung ist, welche des Nachts mit Sturm übergehen soll. […] Shunday qilib, kel kelayotgan Freyheit va Gebäude o'ldi, shuning uchun Zerrüttung von allen Seiten, unde we we am Ende nicht mehr, davon stehen bleiben kann edi.[10]

Despotizmning afzalligi shundaki, u izchil. Uning talablari qanchalik kelishmovchilik bo'lishi mumkin, ular izchil va tizimli. […] Shuningdek, Rim-katolik tamoyillariga binoan cherkov konstitutsiyasi: […] Agar siz uning barcha talablariga rioya qilsangiz, nima qilishni bilasiz. Sizning binoingiz barpo etilgan va uning barcha qismlarida mukammal sukunat hukm surmoqda. Monteskyoning e'tiroziga ko'ra, faqat dahshatli sukunat turiga binoan, siz kechqurun bo'ronga o'tmasdan qal'ada topasiz. […] Ammo erkinlik ushbu binoda biror narsani ko'chirishga jur'at etishi bilan, hamma joyda buzilish xavfi tug'iladi. Shunday qilib, oxirida binoning qaysi qismi buzilmasligini bilmayapsiz.

Insonning tabiiy holati - bu murosasizlik (Tomas Xobbes)

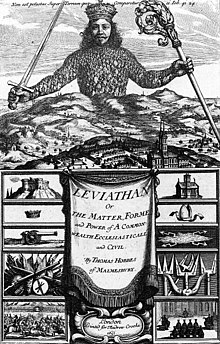

Bu erkinlik nuqtai nazaridan u yaqinlashdi Tomas Xobbs '"har bir insonning har bir odamga qarshi urushi" ssenariysi (bellum omnium kontra omnes) Hobbes o'z kitobida "insoniyatning tabiiy holati" deb ta'riflagan Leviyatan:

Stand der Natur sey Stand allgemeinen Aufruhrs, des Krieges aler kengroq allexem jeder magda, er kann edi; alles Recht ist, wozu man Macht shapka. Dieser unglückselige Zustand habe so lange gedauert, bis die Menschen übereingekommen, ehrem Elende ein Ende zu machen, auf Recht und Macht, in we we es es die exffentliche Sicherheit betrift, Verzicht zu thun, solche einer festgesetz die inger Obge sey dasjenige Recht, was diese Obrigkeit befielt.Für bürgerliche Freyheit hatte er entweder keinen Sinn, oder wollte sie lieber vernichtet, als so gemißbraucht sehen. […] Alles Recht guruhi, tizim tizimlari, auf Macht, Verbindlichkeit auf Furcht; da nun Gott der Obrigkeit va Macht unendlich überlegen ist; shunday qilib, Recht Gottes unendlich über das Recht der Obrigkeit erhaben, and die Furcht vor Gott verbinde uns zu Pflichten, die keiner Furcht vor der Obrigkeit weichen dürfen.[11]

[Gobbsning fikriga ko'ra] tabiatning holati oddiy g'alayonning holati edi, a har bir insonning har bir odamga qarshi urushi, unda hamma qilishi mumkin u nima qila oldi; bunda faqat kuch bor ekan, hamma narsa to'g'ri bo'ladi. Ushbu noxush holat erkaklar o'zlarining azob-uqubatlarini tugatishga va jamoat xavfsizligi masalasida huquq va hokimiyatdan voz kechishga rozi bo'lgunga qadar davom etdi. Va ikkalasini ham tanlangan hokimiyat qo'liga topshirishga kelishib oldilar. Bundan buyon ushbu hokimiyat buyurgan narsa to'g'ri edi, u [Tomas Xobbes] yoki fuqarolik erkinligi to'g'risida hech qanday tasavvurga ega emas edi yoki u shunchaki uni suiiste'mol qilishdan ko'ra uni yo'q qilishni afzal ko'rdi. […] Uning tizimiga ko'ra, barchasi to'g'ri ga asoslangan kuchva barchasi umumiy ma'noda kuni qo'rquv. Xudo o'z qudrati bilan har qanday [dunyoviy] hokimiyatdan cheksiz ustun bo'lgani uchun, Xudoning huquqi ham har qanday hokimiyat huquqidan cheksiz ustundir. Xudodan bo'lgan bu qo'rquv bizni majburiyatlarga majburlaydi, ularni hech qachon biron bir hokimiyat qo'rquvi tufayli tark etmaslik kerak.

Xudodan qo'rqish din tomonidan taqiqlangan bu tabiiy insoniy holatdan (yilda.) Bosse olomon tomonidan tuzilgan frontispiece), Mendelssohn davlatning rolini (qilich ostidagi chap ustun) va dinning rolini (firibgar ostidagi o'ng ustun) va yo'lni, ikkalasi ham qanday ishlashlari kerakligini aniqladi. uyg'unlikka erishish:

Der Staat gebietet und zwinget; die Din belehrt und überredet; der Staat ertheilt Gesetze, vafot Din Gebote. Der Staat hat physische Gewalt und bedient sich derselben, wo es nöthig ist; die Macht der Religion ist Liebe und Wohlthun.[12]

Davlat buyruqlar va majburlovlarni beradi; din tarbiyalaydi va ishontiradi; davlat qonunlarni e'lon qiladi, din ko'rsatmalar beradi. Davlat jismoniy kuchga ega va kerak bo'lganda uni ishlatadi; dinning kuchi xayriya va xayr-ehson.

Ammo, qaysi dinni davlat bilan uyg'unlikda saqlash zarur bo'lsa, davlat dunyoviy hokimiyat sifatida hech qachon o'z fuqarolarining e'tiqodi va vijdoni to'g'risida qaror qabul qilishga haqli emas.

Tomas Xobbsda Leviyatan Xudodan qo'rqish ham davlatni past kuch sifatida yaratgan degan dalil, xristian Patristikda juda keng tarqalgan diniy an'analardan olingan va uni qabul qilish Tanax. Mendelson, shubhasiz, Xobbesning axloqiy falsafasidan frantsuzlar va Xabsburg monarxiyasi va uning Rim-katolik konstitutsiyasidagi hozirgi sharoitga murojaat qilish uchun foydalangan, ammo uning asosiy manzili, ehtimol Prussiya va uning "faylasuf qirol ".

Ammo Mendelsonning Gobbs ustidan "g'alaba qozonishi" Gobbsning inson tabiatidagi holati o'zining siyosiy nazariyasi uchun muhim emasligini anglatmas edi. Hobbesning ijtimoiy shartnomani ta'sirchan asoslashi ritorik ehtiyojlar uchun ancha foydaliroq edi Xaskalah dan Russo "s contrat sociale, chunki uning axloqiy falsafasi siyosiy hokimiyatni suiiste'mol qilish oqibatlarini juda chuqur aks ettiradi. Va davlat dinidan boshqa e'tiqodga ega bo'lgan barcha zamondoshlar bu oqibatlarga juda yaxshi tanish edilar.

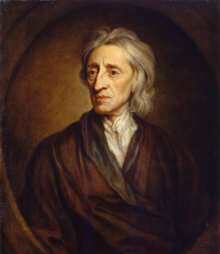

Bag'rikenglik shartnomasi (Jon Lokk)

"Vijdon erkinligi" toifasi orqali (Gewissensfreiheit) Mendelssohn qorong'u tomondan ("har bir odamning har bir odamga qarshi urushi") tomon burildi Jon Lokk "bag'rikenglik" ning ma'rifiy ta'rifi va uning din bilan davlatni ajratish kontseptsiyasiga:

Locke, der in denselben verwirrungsvollen Zeitläuften lebte, suchte die Gewissensfreyheit auf eine andre Weise zu schirmen. Seinen In Shorten über die Toleranz legt er die Definition zum Grunde: Ein Staat sey eine Gesellschaft von Menschen, die sich vereinigen, um ihre zeitliche Wohlfarth gemeinschaftlich zu befördern. Hieraus folgt alsdann ganz natürlich, daß der Staat sich um die Gesinnungen der Bürger, ifre ewige Glückseligkeit betreffend, gar nicht zu bekümmern, sondern jeden zu dulden habe, der sich burgerlich gut auffüxt in gigen gerch, ixteich inchit, ixtenxit, menxter, amsterdam hinderlich ist. Der Staat, al Staat, hat auf keine Verschiedenheit der Religionen zu sehen; denn Religion hat an und für sich auf das Zeitliche keinen nothwendigen Einfluß, and stehet blos durch die Verbindung-da Willkühr der Menschen mit demselben.[13]

Bir vaqtning o'zida [Gobbs singari] chalkashliklarga to'la yashagan Lokk vijdon erkinligini himoya qilishning boshqa usulini izladi. O'zining bag'rikenglik haqidagi maktublarida u o'zining ta'rifini quyidagicha asoslagan: Davlat insonlarni birlashishi kerak, ular birgalikda ularni qo'llab-quvvatlashga kelishgan. vaqtinchalik farovonlik. Bundan kelib chiqadigan narsa tabiiyki, davlat fuqaroning ularning abadiy e'tiqodiga bo'lgan munosabati to'g'risida g'amxo'rlik qilmasligi kerak, aksincha fuqarolik hurmati bilan harakat qiladigan har bir kishiga toqat qilishi kerak, ya'ni o'z fuqarolariga ularning vaqtinchalik e'tiqodiga to'sqinlik qilmasligi kerak. Davlat, fuqarolik hokimiyati sifatida, kelishmovchiliklarni kuzatmasligi kerak edi; chunki din o'z-o'zidan vaqtincha ta'sir qilishi shart emas edi, chunki u odamlarning o'zboshimchaliklari bilan bog'liq edi.

Lokkning bag'rikenglik holati va unga fuqaro sifatida bog'langan insonlar o'rtasidagi munosabati ijtimoiy shartnoma bilan ta'minlanishi kerak edi. Muso Mendelson ushbu shartnomaning mavzusini "mukammal" va "nomukammal" deb ta'riflaganda oddiy sud maslahatiga amal qildi. "huquqlar" va "javobgarlik":

Es giebt vollkommene und unvollkommene, sowohl Pflichten, va boshqalar Rechte. Jene heißen Zwangsrechte und Zwangspflichten; diese hingegen Ansprüche (Tishlangan) und Gewissenspflichten. Jene sind äusserlich, diese nur innerlich. Zwangsrechte dürfen mit Gewalt erpreßt; Tishlangan aber verweigert edi. Unterlassung der Zwangspflichten ist Beleidigung, Ungerechtigkeit; der Gewissenpflichten aber blos Unbilligkeit.[14]

Barkamol va nomukammal, shuningdek, majburiyatlar - huquqlar mavjud. Birinchisi "majburiy huquqlar" va "majburiy majburiyatlar", ikkinchisi "talablar" (so'rovlar) va "vijdonning javobgarligi" deb nomlanadi. Birinchisi rasmiy, ikkinchisi faqat ichki. Majburiy huquqlarni amalga oshirishga, shuningdek so'rovlarni rad etishga yo'l qo'yiladi. Majburiy majburiyatlarni e'tiborsiz qoldirish - bu haqorat va adolatsizlik; ammo vijdonning javobgarligini e'tiborsiz qoldirish faqat adolatsizlikdir.

Mendelsonning ijtimoiy shartnomasiga binoan davlat va din o'rtasidagi bo'linish "rasmiy" va "ichki" tomonlarni ajratib turishga asoslangan edi. Shuning uchun din o'z-o'zidan ijtimoiy shartnomaning "rasmiy" sub'ekti emas edi, faqat "rasmiy huquq" yoki "javobgarlik" ni buzgan taqdirdagina, fuqaroning xatti-harakatlari hukm qilinishi kerak edi. Bu dinni siyosiy nazariyadan ajratib olish va xususiy sohaga qisqartirishiga qaramay, har bir din ikkinchi qismida Mendelson ta'riflagan o'ziga xos "ichki" kuchga ega edi.

Diniy masala (ikkinchi qism)

Muso Mendelson o'zining siyosiy nazariyasida Prussiya davlatining hozirgi sharoitini tanqid qilishi kerak edi va u buni eslatmasdan qisman senzuraga va qisman ritorik sabablarga ko'ra qilgan. Bu uning regenti o'zining falsafasidan asrlar ortda qolgan deb aytish uchun uning muloyim usuli edi:

Ich habe das Gluk, einem Staate zu leben, welchem diese meine Begriffe weder neu, noch sonderlich auffallend sind. Der weise Regent, von dem er beherrscht wird, hat es, seit Anfang seiner Regierung, beständig sein Augenmerk seyn lassen, Menschheit in Glaubenssachen, ihr volles Recht einzusetzen. […] Mit Weiser Mäßigung hat zwar Vorrechte der äußern Religion geschont, in Besen er sie gefunden. Noch gehören vielleicht Jahrhunderte von Cultur und Vorbereitung dazu, bevor die Menschen begreifen werden, daß Vorrechte um der Religion willen weder rechtlich, noch im Grunde nutzlich seyen, and da es es eine wahre wench whech gerch Wenchter Wuhdchen Werchench Werchuten Wuhercht Wuhercht germaniyaliklar . Indessen hat sich die Nation unter der Regierung weesen so sehr an Duldung und Vertragsamkeit in Glaubenssachen gewöhnt, daß Zwang, Bann und Ausschließungsrecht wenigstens aufgehört haben, populé Begriffe zu seyn.[15]

Mening fikrlarim yangi bo'lmagan va juda g'ayrioddiy bo'lmagan holatda yashash baxtiga muyassar bo'ldim. Uni boshqaradigan dono regent, hukmronligi boshlanganidan buyon, insoniyat barcha imon ishlariga nisbatan to'liq huquqqa ega bo'lishiga doimo e'tibor qaratgan [so'zma-so'z: ishonish, tan olish]. […] U dono mo''tadillik bilan rasmiy dinning imtiyozini o'zi topganidek saqlab qoldi. Bizning oldimizda hali bir necha asrlik tsivilizatsiya va tayyorgarlik turibdi, qachonki inson ma'lum bir dinning imtiyozlari na qonunga va na dinning asosiga asoslanmasligini tushunadi, shunda shunchaki foydasiga har qanday fuqarolik kelishmovchiligini bekor qilish haqiqiy foyda keltiradi. bitta din. Ammo bu Dono hukmronligi ostida millat boshqa dinlarga nisbatan bag'rikenglik va muvofiqlikka shunchalik odatlanib qolganki, hech bo'lmaganda kuch ishlatish, taqiqlash va chetlatish huquqi endi keng tarqalgan atama emas.

Natijada diniy hokimiyatning ikkinchi qismi u hayot davomida doimo himoya qilishi kerak bo'lgan ushbu dinning hozirgi sharoitlarini tanqid qilishi kerak edi. Ushbu tanqidchilar uchun unga davlat va din bo'linishi kerak, lekin birdamlikda saqlanishi kerakligi, shuningdek, diniy jamoatning siyosiy maqsadi bo'lishi kerak bo'lgan adolatli davlatning utopik postulatsiyasi zarur edi. Ushbu tayyorgarlikdan so'ng uning siyosiy nazariyasida old shartlarni topish (kalit yoki yaxshiroq: the uzuk uning butun argumentatsiyasida) birinchi qadam noto'g'ri qabul qilingan fikrlarni sharhlash edi: despotizmga moslashish, chunki bu ko'plab xristianlar tomonidan "yahudiylarning melioratsiyasi" ni muhokama qilgan.

Yuqori qavatga tushish (Lavater va Kranz)

Shuning uchun Muso Mendelson o'z bahsida ishlatgan eski dalillariga ishora qiladi Lavater - va yaqinda Mendelsonning kirishining noma'lum uzilishiga javoban Menassa Ben Isroil "s Yahudiylarning oqlanishi.[16] O'rta asr metaforasi bilan xotira san'ati (ko'pincha allegorik tarzda "ehtiyotkorlik ") va uning diniy ta'limga axloqiy va sentimental ta'lim sifatida murojaat qilishi, u Lavaterning proektsiyasini orqaga qaytarishga urindi. Xristianlar yahudiylik inqirozini ko'rib chiqishni yaxshi ko'rsalar ham, Mendelson hozirgi vaziyatni - arafasida Frantsiya inqilobi - dinning umumiy inqirozi sifatida:

Wenn es wahr ist, vack Ecksteine meines Hauses austreten, and das Gebäude einzustürzen drohet, is es wohlgethan, wenn ich meine Habseligkeit aus dem untersten Stokwerke in das oberste rette? Bin ich ham sicherer? Christentum, Wie Sie wissen, auf dem Judentume gebauet, und not notwwendig, wenn dieses fällt, mit ehen eauen Hauffen stürzen.[17]

Agar rost bo'lsa, uyimning toshlari shu qadar zaiflashdiki, bino qulab tushishi mumkin edi, men mollarimni yerdan yuqori qavatga saqlash bo'yicha maslahatga amal qilaymi? U erda men xavfsizroq bo'lamanmi? Ma'lumki, nasroniylik yahudiylik diniga asoslanadi va shuning uchun agar ikkinchisi qulab tushsa, birinchisi uning ustiga bir uyum ostida qulab tushadi.

Birinchi qism boshidan Mendelsonning uy metaforasi ikkinchi qism boshida yana paydo bo'ladi. Bu erda u xristianlik hech qachon o'ziga xos axloq qoidalarini rivojlantirmaganligi haqidagi tarixiy haqiqatni aks ettirish uchun foydalangan o'nta amr, ular hanuzgacha Masihiy Injilning kanonik redaktsiyasining bir qismi hisoblanadi.

Lavater bu erda munozarali dindorning ozmi-ko'pmi mo''tadil misoli bo'lib xizmat qiladi, uning dini siyosiy tizimda eng ma'qul va hukmron hisoblanadi. Hobbes stsenariysida bo'lgani kabi, unga tizim nima qilishiga imkon beradi - hech bo'lmaganda bunday holatda: boshqa fuqaroni hukmron dinga o'tishga majbur qilish.

Yahudiylar teng fuqarolar sifatida va yahudiylik inqirozi (Haskalah islohoti)

Ammo bu ikkiyuzlamachilik yana bir bor Muso Mendelsonning bag'rikenglik shartnomasining radikalizmini aks ettiradi: Agar dinning biznesini "ichki tomoniga" kamaytirish kerak bo'lsa va dinning o'zi bu shartnomaning rasmiy mavzusi bo'lishi mumkin emas bo'lsa, demak, bu shunchaki davlat ishlari kabi davlat ishlarini anglatadi. ijro etuvchi, qonun chiqaruvchi va sud tizimi endi diniy ishlar bo'lmaydi. Shunga qaramay, u ko'pgina pravoslav yahudiylar uchun deyarli qabul qilinmaydigan rabbin yurisdiksiyasining zamonaviy amaliyotini inkor etdi. Va uning kitobi nashr etilganidan bir yil o'tgach, ravvin yurisdiktsiyasini rad etish siyosiy amaliyotga aylandi Xabsburg monarxiyasi "bag'rikenglik patenti" ga qo'shib qo'yilgan davlat farmoni bilan yahudiy sub'ektlarini xristian sub'ektlari bilan teng ravishda o'zlarining sud sudlariga topshirdilar.

Muso Mendelson hozirgi sharoitni va unga biriktirilgan rabinlik amaliyotini inkor etgan o'z davrining birinchi maskilimi bo'lishi kerak edi. Bu shart har bir yahudiy jamoasining o'z vakolatiga ega bo'lishi va bir nechta jamoalarning birgalikdagi hayoti ko'pincha sudyalarni tuzatishi edi. Uning taklifi nafaqat juda zamonaviy deb hisoblanishi kerak, balki munozaralar paytida bu juda muhim bo'lgan Frantsiya qonunchilik assambleyasi haqida Yahudiylarning ozodligi 1790 yillar davomida. Ushbu bahs-munozaralarda yahudiylik ko'pincha "millat ichida o'z millati" bo'lishi kerak edi va yahudiylar vakillari avvalgi maqomidan voz kechishlari kerak edi, shunda yahudiy aholisi teng huquqli fuqarolar sifatida yangi maqomga ega bo'lishlari va ular yangi qonunda ishtirok etishlari kerak edi. Frantsiya konstitutsiyasining.

O'zining pragmatizmida Mendelson yahudiy aholisini rabbonlar yurisdiksiyasi an'analaridan voz kechish kerakligiga ishontirishi kerak edi, lekin shu bilan birga ular o'zlarini pastroq his qilishlari uchun hech qanday sabab yo'q, chunki ba'zi nasroniylar yahudiy urf-odatlarining axloqiy sharoitlari deb hisoblashlari kerak. absolutsiyaning teologik kontseptsiyasidan past.

Masihiylarning qonunlari bo'lgan o'zlarining asoslariga qaytish yo'lini topish nasroniylarga bog'liq edi. Ammo yahudiy jamoalari boy va imtiyozli ozchilik tomonidan tashlab qo'yilgan hozirgi vaziyatga duch kelish yahudiylarga bog'liq edi, shuning uchun qashshoqlik tez sur'atlarda o'sib bormoqda - ayniqsa shahar gettolarida. Muso Mendelson o'z falsafasida jamoalar o'rtasida o'rta asrlar sharoitining o'zgarishiga, badavlat va ravvin oilalari orasidagi elita jamiyatni boshqarayotgan paytda munosabat bildirgan. Prussiya davlati tomonidan jamiyatning boy a'zolariga yangi imtiyozlar berildi, shunda ular oxir-oqibat konversiya orqali jamoadan chiqib ketishdi. Ammo Mendelssohn naflilikni badavlat a'zolarning ixtiyoriy harakati sifatida emas, balki "majburiy javobgarlik" sifatida kamroq ko'rib chiqardi.

The uzuk (Lessing va deizm)

Muso Mendelson zamondagi gumanistik idealizmni va uni birlashtirgan sinkretizmni yaratdi deistik hayotiy an'ana bilan oqilona tamoyillarga asoslangan tabiiy din tushunchasi Ashkenasic Yahudiylik. Uning Musa qonuniga sig'inishini tarixiy tanqidning bir turi sifatida noto'g'ri tushunmaslik kerak, chunki u o'zining siyosiy motivli talqiniga asoslangan edi Tavrot Muso payg'ambarga taqdim etilgan ilohiy vahiy sifatida, u ilohiy qonun bilan oltin buzoq va butparastlikka sig'inish ramzi bo'lgan yahudiylikni moddiy tanazzuldan xalos qiladi.

Musa Mendelson uchun Muso qonuni "ilohiy" edi, agar uning printsiplariga rioya qilgan jamoat adolatli bo'lsa. "Ilohiy" atributga qonunning adolatli ijtimoiy tarkibni yaratish funktsiyasi berilgan: ijtimoiy shartnoma o'z-o'zidan. Qonunning abadiy haqiqati ushbu funktsiyaga bog'liq edi va u shunchalik kam erishilgandiki, ravvinning har qanday hukmini Salomonik Hikmatiga ko'ra hukm qilish kerak edi. Mendelssohn ning bir latifasiga ishora qildi Xill maktabi ning Mishna o'z-o'zidan teologik formulaga ega kategorik imperativ Kant keyinroq uni chaqirganidek:

Ein Xayde spraisi: Rabvin, lehret mich das ganze Gesetz, indem ich auf einem Fuße stehe! Samay, dem er diese Zumuthung vorher ergehen ließ, hatte ihn mit Verachtung abgewiesen; allein der durch seine unüberwindliche Gelassenheit und Sanftmuth berühmte Hillel sprach: Sohn! liebe deinen Nächsten wie dich selbst. Dieses ist der Text des Gesetzes; alles übrige ist Kommentar. Nun gehe hin und lerne![18]

Goy dedi: "Ustoz, menga bitta oyoq bilan turadigan butun qonunni o'rgating!" Ilgari u xuddi shu beparvolik bilan murojaat qilgan Shammai, unga beparvolik bilan rad etdi. Ammo o'zining tinchlanmaydigan tinchligi va yumshoqligi bilan mashhur bo'lgan Xilll javob berdi: "O'g'il! Qo'shningni o'zing kabi sev. [Levilar 19:18] Bu qonun matni, qolganlari sharh. Endi borib o'rganing!"

Yangi Ahdda tez-tez keltirilgan bibliyada keltirilgan ushbu maqol bilan tez-tez dadillik, shu jumladan Mendelson yahudiy-nasroniylarning umumbashariy axloqqa qo'shgan hissasi sifatida Muso qonunining deistist sig'inishiga qaytdi:

Diese Verfassung bizning einziges Mal da gewesen: nennet sie die mosaische Verfassung, bey ihrem Einzelnamen. Allwissenden allein bekannt, Bey Welchem Volke und in Welchem Jahrhunderte sich etwas, Aehnliches wieder wird sehen lassen.[19]

Konstitutsiya bu erda faqat bir marta bo'lgan: siz uni deb atashingiz mumkin mozaika Konstitutsiyasi, bu uning nomi edi. U g'oyib bo'ldi va faqat Qodir Xudo biladi, qaysi millat va qaysi asrda yana shunga o'xshash narsa paydo bo'ladi.

"Mosaik konstitutsiyasi" - bu ota-bobolari aytganidek, demokratik konstitutsiyaning yahudiy nomi edi. Ehtimol, ba'zi yahudiylar bir vaqtlar ularni feodal qulligidan xalos qiladigan Masih kabi kutishgan.

U dramasida Lessingni ilhomlantirgan dalil Natan der Vayz, quyidagilar edi: Har bir din o'z-o'zidan hukm qilinmasligi kerak, faqat adolatli qonunga binoan, u bilan birga bo'lgan fuqaroning harakatlari. Ushbu turdagi qonun adolatli davlatni tashkil etadi, unda turli xil e'tiqoddagi odamlar birgalikda tinch-totuv yashashlari mumkin.

Uning falsafasiga ko'ra, har qanday dinning yangi ayblovi yurisdiktsiya emas, balki adolatli fuqaro bo'lish uchun zarur tayyorgarlik sifatida ta'lim edi. Mendelsonning fikriga ko'ra, yahudiy bolasi bir vaqtning o'zida nemis va ibroniy tillarini o'rganishga jalb qilinishi uchun Maymonid singari klassik muminiy mabbonik mualliflarini ibroniy tilidan nemis tiliga tarjima qilgan.[20]

Muso Mendelsonning fuqarolik sharoitlarini baholashi (1783)

At the end of his book Mendelssohn returns to the real political conditions in Habsburg, French and Prussian Monarchy, because he was often asked to support Jewish communities in their territories. In fact none of these political systems were offering the tolerant conditions, so that every subject should have the same legal status regardless to his or her religious faith. (In his philosophy Mendelssohn discussed the discrimination of the individuum according to its religion, but not according to its gender.) On the other hand, a modern education which Mendelssohn regarded still as a religious affair, required a reformation of the religious communities and especially their organization of the education which has to be modernized.

As long as the state did not follow John Locke's requirement concerning the "freedom of conscience", any trial of an ethic education would be useless at all and every subject would be forced to live in separation according to their religious faith. Reflecting the present conditions Mendelssohn addresses – directly in the second person – to the political authorities:

Ihr solltet glauben, uns nicht brüderlich wieder lieben, euch mit uns nicht bürgerlich vereinigen zu können, so lange wir uns durch das Zeremonialgesetz äusserlich unterscheiden, nicht mit euch essen, nicht von euch heurathen, das, so viel wir einsehen können, der Stifter eurer Religion selbst weder gethan, noch uns erlaubt haben würde? — Wenn dieses, wie wir von christlich gesinnten Männern nicht vermuthen können, eure wahre Gesinnung seyn und bleiben sollte; wenn die bürgerliche Vereinigung unter keiner andern Bedingung zu erhalten, als wenn wir von dem Gesetze abweichen, das wir für uns noch für verbindlich halten; so thut es uns herzlich leid, was wir zu erklären für nöthig erachten: so müssen wir auf bürgerliche Vereinigung Verzicht thun; so mag der Menschenfreund Dohm vergebens geschrieben haben, und alles in dem leidlichen Zustande bleiben, in welchem es itzt ist, in welchem es eure Menschenliebe zu versetzen, für gut findet. […] Von dem Gesetze können wir mit gutem Gewissen nicht weichen, und was nützen euch Mitbürger ohne Gewissen?[21]

You should think, that you are not allowed to return our brotherly love, to unite with us as equal citizens, as long as there is any formal divergence in our religious rite, so that we do not eat together with you and do not marry one of yours, which the founder of your religion, as far as we can see, neither would have done, nor would have allowed us? — If this has to be and to remain your real opinion, as we may not expect of men following the Christian ethos; if a civil unification is only available on the condition that we differ from the law which we are already considering as binding, then we have to announce – with deep regret – that we do better to abstain from the civil unification; then the philanthropist Dohm has probably written in vain and everything will remain on the awkward condition – as it is now and as your charity has chosen it. […] We cannot differ from the law with a clear conscience and what will be your use of citizens without conscience?

In this paragraph it becomes very evident, that Moses Mendelssohn did not foresee the willingness of some Jewish men and women who left some years later their communities, because they do not want to suffer from a lower legal status any longer.

History of reception

Moses Mendelssohn risked a lot, when he published this book, not only in front of the Prussian authority, but also in front of religious authorities – including Orthodox Rabbis. The following years some of his famous Christian friends stroke him at his very sensible side: his adoration for Lessing who died 1781 and could not defend his friend as he always had done during his lifetime.

Mendelssohn and Spinoza in the Pantheism Controversy

The strike was done by Lavater do'stim Fridrix Geynrix Yakobi who published an episode between himself and Lessing, in which Lessing confessed to be a "Spinozist", while reading Gyote "s Sturm und Drang she'r Prometey.[22] "Spinozism" became quite fashionable that time and was a rather superficial reception, which was not so much based on a solid knowledge of Spinoza's philosophy than on the "secret letters" about Spinoza.[23] These letters circulated since Spinoza's lifetime in the monarchies, where Spinoza's own writings were on the index of the Catholic Inkvizitsiya, and often they regarded Spinoza's philosophy as "atheistic" or even as a revelation of the secrets of Kabala mysticism.[24] The German Spinoza fashion of the 1780s was more a "panteistik " reception which gained the attraction of rebellious "atheism", while its followers are returning to a romantic concept of religion.[25] Jacobi was following a new form of German idealism and later joined the romanticist circle around Fixe Jena shahrida.[26] Later, 1819 during the hep hep tartibsizliklar or pogroms, this new form of idealism turned out to be very intolerant, especially in the reception of Jakob Fries.[27]

Moda panteizm did not correspond to Mendelson 's deistic reception of Spinoza[28] va Lessing whose collected works he was publishing. He was not so wrong, because Spinoza himself developed a fully rational form of deizm in his main work Etika, without any knowledge of the later panteistik reception of his philosophy. Mendelssohn published in his last years his own attitude to Spinoza – not without his misunderstandings, because he was frightened to lose his authority which he still had among rabbis.[29] On his own favor Gyote fashioned himself as a "revolutionary" in his Dichtung und Wahrheit, while he was very angry with Jacobi because he feared the consequences of the latter's publication using Goethe's poem.[30] This episode caused a reception in which Moses Mendelssohn as a historical protagonist and his philosophy is underestimated.

Nevertheless, Moses Mendelssohn had a great influence on other Maskilim va Yahudiylarning ozodligi, and on nearly every philosopher discussing the role of the religion within the state in 19th century Western Europe.

The French Revolution and the early Haskalah reform of education

Mendelssohn's dreams about a tolerant state became reality in the new French Constitution of 1791. Berr Isaac Berr, the Ashkenazic representative in the Qonunchilik majlisi, praised the French republic as the "Messiah of modern Judaism", because he had to convince French communities for the new plans of a Jewish reform movement to abandon their autonomy.[31] The French version of Haskalah, called régénération, was more moderate than the Jewish reform movement in Prussia.[32]

While better conditions were provided by the constitution of the French Republic, the conflict between Orthodox Rabbis and wealthy and intellectual laymen of the reform movement became evident with the radical initiatives by Mendelssohn's friend and student Devid Fridlender Prussiyada.[33] He was the first who followed Mendelssohn's postulations in education, since he founded 1776 together with Isaak Daniel Itzig The Jüdische Freischule für mittellose Berliner Kinder ("Jewish Free School for Impecunious Children in Berlin") and 1778 the Chevrat Chinuch Ne'arim ("Society for the Education of Youth"). His 1787 attempt of a German translation of the Hebrew prayerbook Sefer ha-Nefesh ("Book of the Soul") which he did for the school, finally became not popular as a ritual reform, because 1799 he went so far to offer his community a "dry baptism" as an affiliation by the Lutheran church. There was a seduction of free-thinking Jews to identify the seclusion from European modern culture with Judaism in itself and it could end up in baptism. Sifatida Geynrix Geyn commented it, some tend to reduce Judaism to a "calamity" and to buy with a conversion to Christianity an "entré billet" for the higher society of the Prussian state. By the end of the 18th century there were a lot of contemporary concepts of enlightenment in different parts of Europe, in which humanism and a secularized state were thought to replace religion at all.

Isroil Jeykobson, himself a merchant, but also an engaged pedagogue in charge of a land rabbi in Westphalia, was much more successful than David Friedländer. Like Moses Mendelssohn he regarded education as a religious affair. One reason for his success was the political fact, that Westphalia became part of France. Jacobson was supported by the new government, when he founded in 1801 a boys' school for trade and elementary knowledge in Seesen (a small town near Harz ), called "Institut für arme Juden-Kinder". The language used during the lessons was German. His concept of pedagogy combined the ideas of Moses Mendelssohn with those of the socially engaged Philantropin school which Asoslangan founded in Dessau, inspired by Russo 's ideas about education. 1802 also poor Christian boys were allowed to attend the school and it became one of the first schools, which coeducated children of different faith. Since 1810 religious ceremonies were also held in the first Reform Temple, established on the school's ground and equipped by an organ. Before 1810 the Jewish community of the town had their celebrations just in a prayer room of the school. Since 1810 Mendelssohn needed the instrument to accompany German and Hebrew songs, sung by the pupils or by the community in the "Jacobstempel".[34] He adapted these prayers himself to tunes, taken from famous Protestant chorales. In the charge of a rabbi he read the whole service in German according to the ideas of the reformed Protestant rite, and he refused the "medieval" free rhythmic style of chazzan, as it was common use in the other Synagogues.[35] 1811 Israel Jacobson introduced a "confirmation" ceremony of Jewish boys and girls as part of his reformed rite.

Conflicts in Prussia after the Viennese Congress

Since Westphalia came under Prussian rule according to the Vena kongressi 1815, the Jacobson family settled to Berlin, where Israel opened a Temple in his own house. The orthodox community of Berlin asked the Prussian authorities to intervene and so his third "Jacobstempel" was closed. Prussian officers argued, that the law allows only one house of Jewish worship in Berlin. In consequence a reformed service was celebrated as minyan in the house of Jacob Herz Beer. The chant was composed by his son who later became a famous opera composer under the name Giacomo Meyerbeer. In opposition to Israel's radical refuse of the traditional Synagogue chant, Meyerbeer reintegrated the chazzan and the recitation of Pentateuch and Prophets into the reformed rite, so that it became more popular within the community of Berlin.

Johann Gottfried Herder 's appreciation of the Mosaic Ethics was influenced by Mendelssohn's book Quddus as well as by personal exchange with him. It seems that in the tradition of Christian deistic enlightenment the Torah was recognized as an important contribution to the Jewish-Xristian tsivilizatsiyasi, though contemporary Judaism was often compared to the decadent situation, when Aaron created the golden calf (described in Exodus 32), so enlightenment itself was fashioning itself with the archetypical role of Moses.[36] But the contemporary Jewish population was characterized by Herder as a strange Asiatic and selfish "nation" which was always separated from others, not a very original conception which was also popular in the discussions of the National Assembly which insisted that Jewish citizens have to give up their status as a nation, if they want to join the new status as equal citizens.

Jorj Vilgelm Fridrix Hegel whose philosophy was somehow inspired by a "Mosaic" mission, was not only an important professor at the University in Berlin since 1818, he also had a positive influence on reform politics of Prussia. Though his missionary ambitions and his ideas about a general progress in humanity which can be found in his philosophy, Hegel was often described by various of his students as a very open minded and warm hearted person who was always ready to discuss controversially his ideas and the ideas opposed to it. He was probably the professor in Prussia who had the most Jewish students, among them very famous ones like Geynrix Geyn va Lyudvig Byorne, and also reform pedagogues like Nachman Krochmal from Galicia.

When Hegel was still in Heidelberg, he was accusing his colleague Jakob Fries, himself a student of Fixe, for his superstitious ideas concerning a German nation and he disregarded his antisemitic activities as a mentor of the Burschenschaft which organized the Wartburgfest, qotillik Avgust fon Kotzebue va hep hep riots. In 1819 he went with his students to the hep hep riot in Heidelberg and they were standing with raised arms before the people who lived in the poverty of the Jewish ghetto, when the violent mob was arriving.[37] As result he asked his student Friedrich Wilhelm Carové to found the first student association which also allows access for Jewish students, and finally Eduard Gans founded in November the Verein für Kultur und Wissenschaft der Juden [Society for Culture and Science of the Jews] on the perspective that the ideas of enlightenment must be replaced by a sintez of European Jewish and Christian traditions. This perspective followed some fundamental ideas which Hegel developed in his dialectic philosophy of history, and it was connected with hopes that finally an enlightened state will secularize religious traditions and fulfill their responsibility. In some respect this sintez was expected as a kind of revolution, though an identification with the demagogues was not possible—as Heinrich Heine said in a letter 1823:

Obschon ich aber in England ein Radikaler und in Italien ein Carbonari bin, so gehöre ich doch nicht zu den Demagogen in Deutschland; aus dem ganz zufälligen und g[e]ringfügigen Grunde, daß bey einem Siege dieser letztern einige tausend jüdische Hälse, und just die besten, abgeschnitten werden.[38]

Even though I am a Radical in Britain and a Carbonari in Italy, I do certainly not belong to the demagogues in Germany—just for the very simple reason that in case of the latter's victory some thousand Jewish throats will be cut—the best ones first.

In the last two years Prussia passed many restrictive laws which excluded Jews from military and academic offices and as members of parliament. The expectation that the Prussian state will once follow the reasons of Hegel's Weltgeist, failed, instead it was turning backwards and the restrictions increased up to 1841, whereas the officer Dohm expected a participation as equal citizens for 1840. Moses Mendelssohn who was regarded as a Jewish Luther by Heinrich Heine, made several predictions of the future in Quddus. The worst of them became true, and finally a lot of Jewish citizens differed from the law and became what Mendelssohn called "citizens without conscience". Because there was no "freedom of conscience" in Prussia, Geynrix Geyn chap Verein without any degree in law and finally—like Eduard Gans himself—converted to the Lutheran church 1825.

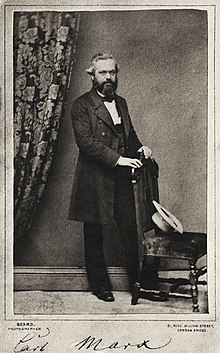

Musa Mendelsonning Quddus and the rise of revolutionary antisemitism

Karl Marks was not a direct student of Hegel, but Hegel's philosophy, whose lectures were also frequented by Prussian officers, was still very present after his death in 1831 as well among conservatives as among radicals who were very disappointed about the present conditions and the failed reform of the state. 1835, when Karl inscribed as a student, Hegel's book Leben Jesu was published posthumously and its reception was divided into the so-called Right or Old and the Left or Yosh gegelliklar atrofida Bruno Bauer va Lyudvig Feyerbax. Karl had grown up in a family which were related to the traditional rabbinic family Levi through his mother. Because the Rhine province became part of the French Republic, where the full civil rights were granted by the Constitution, Marx's father could work as a lawyer (Justizrat) without being discriminated for his faith. This changed, when the Rhine province became part of Prussia after the Congress of Vienna. 1817 yilda Geynrix Marks felt forced to convert to the Lutheran church, so that he could save the existence of his family continuing his profession.[39] In 1824 his son was baptized, when he was six years old.

The occasion that the Jewish question was debated again, was the 7th Landtag of the Rhine province 1843. The discussion was about an 1839 law which tried to withdraw the Hardenberg edict from 1812. 1839 it was refused by the Staatsrat, 1841 it was published again to see what the public reactions would be. The debate was opened between Ludwig Philippson (Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums) and Carl Hermes (Kölnische Zeitung). Karl Marx was thinking to join the debate with an own answer of the Jewish question, but he left it to Bruno Bauer. His later answer was mainly a reception of Bauer's argument. Marx's and Bauer's polemic style was probably influenced by Geynrix Geyn "s Damascus letters (Lutetia Teil 1, 1840) in which Heine was calling Jeyms Mayer de Rotshild a "revolutionary" and in which he used phrases such as:

Bey den französischen Juden, wie bey den übrigen Franzosen, ist das Gold der Gott des Tages und die Industrie ist die herrschende Religion.[40]

For French Jews as well for all the other French gold is the God of the day and industry the dominating religion!

Whereas Hegel's idea of a humanistic secularization of religious values was deeply rooted in the idealistic emancipation debates around Mendelssohn in which a liberal and tolerant state has to be created on the fundament of a modern (religious) education, the only force of modernization according to Marx was capitalism, the erosion of traditional values, after they had turned into material values. Orasidagi farq ancien rejimi and Rothschild, chosen as a representative of a successful minority of the Jewish population, was that they had nothing to lose, especially not in Prussia where this minority finally tended to convert to Christianity. But since the late 18th century the Prussian Jews were merely reduced to their material value, at least from the administrative perspective of the Prussian Monarchy.

Marx's answer to Mendelssohn's question: "What will be your use of citizens without conscience?" was simply that: The use was now defined as a material value which could be expressed as a sum of money, and the Prussian state like any other monarchy finally did not care about anything else.

Der Monotheismus des Juden ist daher in der Wirklichkeit der Polytheismus der vielen Bedürfnisse, ein Polytheismus, der auch den Abtritt zu einem Gegenstand des göttlichen Gesetzes macht. Das praktische Bedürfniß, der Egoismus ist das Prinzip der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft und tritt rein als solches hervor, sobald die bürgerliche Gesellschaft den politischen Staat vollständig aus sich herausgeboren. Der Gott des praktischen Bedürfnisses und Eigennutzes ist das Geld.Das Geld ist der eifrige Gott Israels, vor welchem kein andrer Gott bestehen darf. Das Geld erniedrigt alle Götter des Menschen, - und verwandelt sie in Waare.[41]

Behind Jewish monotheism is the polytheism of various needs, a polytheism which turns even a doormat into an object of the divine law. The practical need, the egoism is the fundament of the fuqarolik jamiyati and itself finally emerges clearly, when a civil society has born its own political state entirely. The God of the practical need and self-interest bo'ladi pul.The money is the busily God of Israel who do not accept any other God beneath himself. The money humiliates all Gods of mankind and turns them into a ware.

Bauer's reference to the golden calf may be regarded a modern form of antisemitism.[42] But Karl Marx turned Bauer's reference into a "syncretism between Mosaic monotheism and Babylonian polytheism". His answer was antisemitic, as far as it was antisemitic that his family was forced to leave their religious tradition for very existential reasons. He hardly foresaw that the rhetorical use of Judaism as a metaphor of capitalism (originally a satirical construction of Heinrich Heine, talking about the "prophet Rothschild") will be constantly repeated in a completely unsatirical way in the history of socialism. Karl Marks used these words in a less satirical than in an antihumanistic way. Its context was the controversy between Old and Young Hegelian and his polemic aimed the "Old Hegelian". He regarded their thoughts as a Prussian form of the ancien rejimi, figured and justified as the humanists, and himself as part of a Jewish privileged minority which was more adapted to modern citizenship than any representative of the Prussian ancien rejimi. While the humanists felt threatened by the industrial revolution, also because they simply feared to lose their privileges, it was no longer the parvenu (kabi Bernard Lazare would call the rich minority later) who needed to be "ameliorated".

Moses Mendelssohn was not mentioned in Marx's answer to the Jewish question, but Marx might have regarded his arguments as an important part of the humanists' approach to ameliorate the Prussian constitution. Nevertheless, Mendelssohn had already discussed the problem of injustice caused by material needs in his way: In Quddus he advised to recompense politicians according to the loss of their regular income. It should not be lower for a rich man, and not higher for a poor. Because if anyone will have a material advantage, just by being a member of parliament, the result cannot be a fair state governing a just society. Only an idealistic citizen who was engaging in politics according to his modern religious education, was regarded as a politician by Moses Mendelssohn.

Mendelssohn's philosophy during the Age of Zionism

Karl Marx's point of view that the idealistic hopes for religious tolerance will be disappointed in the field of politics, and soon the political expectations will disappear in a process of economical evolution and of secularization of their religious values, was finally confirmed by the failure of the 1848 yilgi inqilob. Though the fact that revolutionary antisemitism was used frequently by left and right wing campaigners, for him it was more than just rhetoric. His own cynical and refusing attitude concerning religion was widespread among his contemporaries and it was related with the own biography and a personal experience full of disappointments and conflicts within the family. Equal participation in political decisions was not granted by a national law as they hoped, the participation was merely dependent on privileges which were defined by material values and these transformations cause a lot of fears and the tendence to turn backwards. Even in France where the constitution granted the equal status as citizens since 100 years, the Dreyfus ishi made evident that a lot of institutions of the French Republic like the military forces were already ruled by the circles of the ancien rejimi. So the major population was still excluded from participation and could not identify with the state and its authorities. Social movements and emigration to America or to Palestine were the response, often in a combination. The utopies of these movements were sometimes secular, sometimes religious, and they often had charismatic leaders.

1897 there was the Birinchi sionistlar kongressi in Basel (Switzerland), which was an initiative by Teodor Herzl. The Zionist Martin Buber with his rather odd combination of German Romanticism (Fixe ) and his interest in Hasidizm as a social movement was not very popular on the Congress, but he finally found a very enthusiastic reception in a Zionist student association in Prague, which was also frequented by Maks Brod va Franz Kafka.[43] In a time when the Jewish question has become a highly ideological matter mainly treated in a populistic way from outside, it became a rather satirical subject for Jewish writers of Yiddish, German, Polish and Russian language.

Franz Kafka learned Yiddish and Hebrew as an adult and he had a great interest for Hasidizm as well as for rabbinic literature. He had a passion for Yiddish drama which became very popular in Central Europe that time and which brought Yidishcha literature, usually written as narrative prosa, on stage mixed up with a lot of music (parodies of synagogue songs etc.). His interest corresponded to Martin Buber 's romantic idea that Hasidizm was the folk culture of Ashkenazi yahudiylari, but he also realized that this romanticism inspired by Fichte and German nationalism, expressed the fact that the rural traditions were another world quite far from its urban admirers. This had changed since Maskilim and school reformers like Israel Jakobson have settled to the big towns and still disregarded Yiddish as a "corrupt" and uneducated language.

In the parable of his romance Der jarayoni, published 1915 separately as short story entitled Vor dem Gesetz, the author made a parody of a midrash legend, written during the period of early Merkaba mysticism (6th century), that he probably learned by his Hebrew teacher. Bu Pesikhta described Moses' meditation in which he had to fight against Angelic guardians on his way to the divine throne in order to bring justice (the Tavrot ) to the people of Israel.

Somehow it also reflected Mendelssohn's essay in the context of the public debate on the Yahudiylarning savoli during the 1770s and 1780s, which was mainly led by Christian priests and clerics, because this parable in the romance was part of a Christian prayer. A mysterious priest prayed only for the main protagonist "Josef K." in the dark empty cathedral. The bizarre episode in the romance reflected the historical fact that Jewish emancipation had taken place within Christian states, where the separation between state power and the church was never fully realized. There were several similar parodies by Jewish authors of the 19th century in which the Christians dominating the state and the citizens of other faith correspond to the jealous guardians. Unlike the prophet Moses who killed the angel guarding the first gate, the peasant ("ein Mann vom Lande") in the parable is waiting to his death, when he finally will be carried through the gate which was only made for him. In the narration of the romance which was never published during his lifetime, the main protagonist Josef K. will finally be killed according to a judgement which was never communicated to him.

Hannah Arendt's reception of the Haskalah and of the emancipation history

Xanna Arendt 's political theory is deeply based on theological and existentialist arguments, regarding Jewish Emancipation in Prussia as a failure – especially in her writings after World War II. But the earliest publication discussing the Xaskalah with respect to the German debate of the Jewish Question opened by Christian Wilhelm von Dohm and Moses Mendelssohn dates to 1932.[44] Uning inshoida Xanna Arendt takes Herder's side in reviving the debate among Dohm, Mendelson, Lessing va Cho'pon. According to her Moses Mendelssohn's concept of emancipation was assimilated to the pietist concept of Lessing's enlightenment based on a separation between the truth of reason and the truth of history, which prepared the following generation to decide for the truth of reason and against history and Judaism which was identified with an unloved past. Somehow her theological argument was very similar to that of Kant, but the other way round. Uchun Kant as a Lutheran Christian religion started with the destruction and the disregard of the Mosaic law, whereas Herder as a Christian understood the Jewish point of view in so far, that this is exactly the point where religion ends. According to Hannah Arendt the Jews were forced by Mendelssohn's form of Xaskalah to insert themselves into a Christian version of history in which Jews had never existed as subjects:

So werden die Juden die Geschichtslosen in der Geschichte. Ihre Vergangenheit ist ihnen durch das Herdersche Geschichtsverstehen entzogen. Sie stehen also wieder vis à vis de rien. Innerhalb einer geschichtlichen Wirklichkeit, innerhalb der europäischen säkularisierten Welt, sind sie gezwungen, sich dieser Welt irgendwie anzupassen, sich zu bilden. Bildung aber ist für sie notwendig all das, was nicht jüdische Welt ist. Da ihnen ihre eigene Vergangenheit entzogen ist, hat die gegenwärtige Wirklichkeit begonnen, ihre Macht zu zeigen. Bildung ist die einzige Möglichkeit, diese Gegenwart zu überstehen. Ist Bildung vor allem Verstehen der Vergangenheit, so ist der "gebildete" Jude angewiesen auf eine fremde Vergangenheit. Zu ihr kommt er über eine Gegenwart, die er verstehen muß, weil er an ihr beteiligt wurde.[45]

In consequence the Jews have become without history in history. According to Herder's understanding of history they are separated from their own past. So again they are in front of nothing. Within a historical reality, within the European secularized world, they are forced to adapt somehow to this world, to educate themselves. They need education for everything which is not part of the Jewish world. The actual reality has come into effect with all its power, because they are separated from their own past. Culture is the only way to endure this present. As long as culture is the proper perception of the past, the "educated" Jew is depending on a foreign past. One will reach it through a certain present, just because one participated in it.

Although her point of view was often misunderstood as a prejudice against Judaism, because she often also described forms of opportunism among Jewish citizens, her main concern was totalitarianism and the anachronistic mentality of the ancien rejimi, as well as a postwar criticism, which was concerned with the limits of modern democracy. Her method was arguably idiosyncratic. For instance, she used Marsel Prust 's romance "À la recherche du temps perdu " as a historical document and partly developed her arguments on Proust's observations of Faubourg de Saint Germain, but the publication of her book in 1951 made her very popular, because she also included an early analysis of Stalinism.[46] Seven years later she finally published her biographical study about Rahel Varnhagen. Here she concludes that the emancipation failed exactly with Varnhagen's generation, when the wish to enter the Prussian upper society was related with the decision to leave the Jewish communities. According to her, a wealthy minority, which she called parvenues, tried to join the privileges of the ruling elite of Prussia.[47] The term "parvenu" was taken from Bernard Lazare and she regarded it as an alternative to Maks Veber 's term "pariah."

Shuningdek qarang

- Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus theologico-politicus

- Thomas Hobbes' Leviyatan

- Jon Lokknikidir Tolerantlik to'g'risida maktub, Inson tushunchasiga oid insho

- Immanuel Kant's Die Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der blossen Vernunft

- Xaskalah

- Christian Wilhelm von Dohm

- Musa Mendelson

- Gottxold Efrayim Lessing

- Salomon Maymon

- Xartvig Vesseli

- Devid Fridlender

- Johann Caspar Lavater

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- Isroil Jeykobson

Izohlar

- ^ Dohm & 1781, 1783; Ingl. transl.: Dohm 1957.

- ^ Sammlung derer Briefe, welche bey Gelegenheit der Bonnetschen philosophischen Untersuchung der Beweise für das Christenthum zwischen Hrn. Lavater, Moses Mendelssohn, und Hrn Dr. Kölbele gewechselt worden [Collection of those letters which have been exchanged between Mr. Lavater, Moses Mendelssohn, and Mr. Dr. Kölbele on occasion of Bonnet's investigation concerning the evidence of Christianity], Lavater 1774, Zueignungsschrift, 3 (Google Books ).

- ^ Berkovitz 1989, 30-38,60-67.

- ^ Stern & 1962-1975, 8/1585-1599; Ṿolḳov 2000, 7 (Google Books ).

- ^ Christian Konrad Wilhelm von Dohm: Über die Bürgerliche Verbesserung der Juden ("Concerning the amelioration of the civil status of the Jews"), 1781 and 1783. The autograph is now preserved in the library of the Jewish community (Fasanenstraße, Berlin) – Dohm & 1781, 1783; Ingl. transl.: Dohm 1957.

- ^ Wolfgang Häusler described also the ambiguous effects of the "Toleranzpatent" in his chapter Das Österreichische Judentum, yilda Wandruszka 1985.

- ^ Moses Mendelssohn offered 1782 a little history of antisemitism in his muqaddima to his German translation of Mannaseh ben Israel 's "Salvation of the Jews" (Vindiciae Judaeorum translated as "Rettung der Juden "; Engl. transl.: Mendelssohn 1838d, 82).

- ^ There is no doubt about the fact that Prussia profited a lot, allowing Protestant and Jewish immigrants to settle down in its territories.

- ^ The relation was studied thoroughly by Julius Guttmann 1931.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, I. Abschnitt, 4-5.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, I. Abschnitt, 7-8.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, I. Abschnitt, 28.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, I. Abschnitt, 12-13.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, I. Abschnitt, 32.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, II. Abschnitt, 5-9.

- ^ August Friedrich Cranz from Prussia published it under this title and pretended to be Josef von Sonnenfels ("the admirer S***") – a privileged Jew who could influence the politics at Habsburg court. He addressed Mendelssohn directly: Das Forschen nach Licht und Recht in einem Schreiben an Herrn Moses Mendelssohn auf Veranlassung seiner merkwürdigen Vorrede zu Mannaseh Ben Israel (The searching for light and justice in a letter to Mr. Moses Mendelssohn occasioned by his remarkable preface to Mannaseh Ben Israel), "Vienna" 1782 (reprint: Cranz 1983, 73–87; Ingl. tarjima: (Cranz) 1838, 117–145).

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, II. Abschnitt, 25.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, II. Abschnitt, 58.

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, II. Abschnitt, 123.

- ^ Note that Mendelssohn's engagement for German was in resonance with his contemporaries who tried to establish German as an educated language at universities. Nevertheless he refused Yiddish as a "corrupt dialect": Ṿolḳov 2006, 184 (Google Books ).

- ^ Mendelssohn 1783, II. Abschnitt, 131-133.

- ^ Über die Lehre des Spinoza (Jacobi 1789, 19-22) was a reply to Mendelssohn's Morgenstunden (Mendelssohn 1786 ). In an earlier publication Jacobi opposed to Mendelssohn's opinion about Spinoza. On the frontispice of his publication we see an allegoric representation of "the good thing" with a banner like a scythe over a human skeleton (the skull with a butterfly was already an attribute dedicated to Mendelssohn since his prized essay Phädon), referring to a quotation of Immanuil Kant on page 119 (Jacobi 1786, Google Books ). Following the quotation Jacobi defines Kant's "gute Sache" in his way by insisting on the superiority of the "European race". His publication in the year of Mendelssohn's death makes it evident, that Jacobi intended to replace Mendelssohn as a contemporary "Socrate" — including his own opinion about Spinoza.

- ^ W. Schröder: Spinoza im Untergrund. Zur Rezeption seines Werks in der littérature clandestine [The underground Spinoza - On the reception of his works in French secret letters], ichida: Delf, Schoeps & Walther 1994, 142-161.

- ^ Klaus Hammacher: Ist Spinozismus Kabbalismus? Zum Verhältnis von Religion und Philosophie im ausgehenden 17. und dem beginnenden 18. Jahrhundert [Is Spinozism Kabbalism? On the relation between religion and philosophy around the turn to the 18th century], ichida: Hammacher 1985, 32.

- ^ It is astonishing, how superstitious the level of this Spinoza reception was in comparison to that of Spinoza's time among scholars and scientists at the Leyden University: [1] M. Bollacher: Der Philosoph und die Dichter – Spiegelungen Spinozas in der deutschen Romantik [The philosopher and the poets - Reflexions of German romanticism in front of Spinoza], ichida: Delf, Schoeps & Walther 1994, 275-288. [2] U. J. Schneider: Spinozismus als Pantheismus – Anmerkungen zum Streitwert Spinozas im 19. Jahrhundert [Spinozism as Pantheism - Notes concerning the value of the Spinoza reception in 19th century arguments], ichida: Caysa & Eichler 1994, 163-177. [3] About the 17th century reception at Leyden University: Marianne Awerbuch: Spinoza in seiner Zeit [Spinoza in his time], ichida: Delf, Schoeps & Walther 1994, 39-74.

- ^ K. Hammacher: Il confronto di Jacobi con il neospinozismo di Goethe e di Herder [The confrontation between Jacobi and the Neo-Spinozism of Goethe and Herder], ichida: Zac 1978, 201-216.

- ^ P. L. Rose: German Nationalists and the Jewish Question: Fichte and the Birth of Revolutionary Antisemitism, ichida: Atirgul 1990 yil, 117-132.

- ^ Qanchalik Quddus is concerned, Mendelssohn's reception of Spinoza has been studied by Willi Goetschel: "An Alternative Universalism" in Goetschel 2004, 147-169 (Google Books ).

- ^ Mendelssohn published his Morgenstunden mainly as a refute of the pantheistic Spinoza reception (Mendelssohn 1786 ).

- ^ [1] There exists an unverified anecdote in which Herder refused to bring a lent Spinoza book to the library, using this justification: "Anyway there is nobody here in this town, who is able to understand Spinoza." The librarian Goethe was so upset about this insult, that he came to Herder's house accompanied by policemen. [2] About the role of Goethe's Prometey ichida pantheism controversy, Goethe's correspondence about it and his self portrait in Dichtung und Wahrheit: Blumenberg 1986, 428-462. [3] Bollacher 1969.

- ^ Berr Isaac Berr: Lettre d'un citoyen, membre de la ci-devant communauté des Juifs de Lorraine, à ses confrères, à l'occasion du droit de citoyen actif, rendu aux Juifs par le décrit du 28 Septembre 1791, Berr 1907.

- ^ Berkovitz 1989, 71-75.

- ^ On the contemporary evolution of Jewish education → Eigenheit und Einheit: Modernisierungsdiskurse des deutschen Judentums der Emanzipationszeit [Propriety and Unity: Discourses of modernization in German Judaism during the Emancipation period], Gotzmann 2002.

- ^ He published his arrangements, 26 German and 4 Hebrew hymns adapted to 17 church tunes, in a chant book in which the score of the Hebrew songs were printed from the right to the left. Jacobson 1810. In this year he founded a second school in Cassel which was the residence of the Westphalian King Jerome, Napoleonning ukasi.

- ^ Idelsohn 1992, 232-295 (Chapter XII) (Google Books ).

- ^ P.L. Gul: Herder: "Humanity" and the Jewish Question, ichida: Atirgul 1990 yil, 97-109.

- ^ Atirgul 1990 yil, 114.

- ^ Heine in a letter to Moritz Embden, dated the 2 February 1823 — quoted after the Heinrich Heine Portal of University Trier (letter no. 46 according to the edition of "Weimarer Säkularausgabe" vol. 20, p. 70).

- ^ For more interest in Karl Marx' biography see the entry in: "Karl Marx—Philosopher, Journalist, Historian, Economist (1818–1883)". A&E televizion tarmoqlari. 2014 yil.

- ^ Heine 1988, 53. Original text and autograph (please click on "E ") da Heinrich Heine Portal of University Trier. Heinrich Heine sent letters and books to his wife Betty de Rothschild since 1834, and he asked the family for financial support during the 50s.

- ^ Marx 1844, 184; Ingl. tarjima qilish (Yahudiylar savoliga ).

- ^ Paul Lawrence Rose (Atirgul 1990 yil, 263ff; 296ff) used the term "revolutionary antisemitism" and analysed, how it developed between Bauer and Marx.

- ^ Baioni 1984.

- ^ The early essay concerning Lessing, Herder and Mendelssohn: Aufklärung und Judenfrage, Arendt-Stern 1932 was published in a periodical called "Zeitschrift für die Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland". Here Hannah Arendt regarded Moses Mendelssohn, because of his ideas concerning education (history as a teacher) and his negative attitude against Yidishcha, juda sodda va juda idealistik; Shunday qilib, uning fikriga ko'ra, Mendelson zamondosh aholisi o'rtasida haqiqiy ijtimoiy va tarixiy muammolarga duch kela olmadi. getto. Mendelsonni tanqid qilishda u keyingi avlod nima uchun ekanligini tushunishga urindi Maskilim ma'rifat falsafasi bilan taqqoslaganda yahudiy urf-odatlarining pastligiga shunchalik ishonishgan.

- ^ Arendt-Stern 1932 yil, 77.

- ^ Arendt 1951 yil.

- ^ Rahel Varnhagen. Yahudiy ayolning hayoti, Arendt 1957 yil.

Bibliografiya

Nashrlar

- Mendelson, Muso (1783), Quddus: oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum. Fon Musa Mendelson. Mit allergnädigsten Freyheiten, Berlin: Fridrix Maurer, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1787), Quddus oder über religiöse Macht und Judenthum. Fon Musa Mendelson, Frankfurt, Leypsig, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1838), "Quddus, oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum", Sämmtliche Werke - Ausgabe in einem Bande als National-Denkmal, Vena: Verlag fon Mich.Shmidts sel. Vitve, 217–291 betlar, ISBN 9783598518621, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1919), Quddus: oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum, Berlin: Weltverlag, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1983), "Quddus: oder über religiöse Macht und Judentum", Altmannda, Aleksandr; Bamberger, Fritz (tahr.), Moses Mendelssohn: Gesammelte Schriften - Jubiläumsausgabe, 8, Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog, 99–204-betlar, ISBN 3-7728-0318-0.

- Mendelson, Muso (1786), Moses Mendelssohns Morgenstunden va Vorlesungen über das Daseyn Gottes, Berlin: Christian Fridrix Voss und Sohn, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1983a), "Vorwort zu Manasseh ben Israels« Rettung der Juden »", Altmannda, Aleksandr; Bamberger, Fritz (tahr.), Moses Mendelssohn: Gesammelte Schriften - Jubiläumsausgabe, 8, Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog, 89-97 betlar, ISBN 3-7728-0318-0.

- Mendelson, Muso (1927), "Vorwort zu Manasseh ben Israels« Rettung der Juden »", Freydenbergerda, German (tahr.), Men Kampf um vafot etgan Menschenrexte, Frankfurt am Main: Kauffmann, 40-43 betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Arendt-Stern, Xanna (1932), "Aufklärung und Judenfrage", Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Juden Doychlandda, IV (2): 65-77, arxivlangan asl nusxasi 2011 yil 17-iyulda, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Berr, Berr Isaak (1907), "Lettre d'un citoyen, membre de la ci-devant Communauté des Juifs de Lorraine, à ses confrères, àccasion du droit de citoyen actif, rendu aux Juifs par le décrit du 28 Sentyabr 1791 (Nensi 1791) ", Tama, Diogen (tahr.), Parij Oliy Kengashining operatsiyalari, Repr.: London, 11–29 betlar, ISBN 3-7728-0318-0.

- Kranz, Avgust Fridrix (1983), "Das Forschen nach Licht und Recht in einem Schreiben and Herrn Moses Mendelssohn auf Veranlassung seiner merkwürdigen Vorrede zu Mannaseh Ben Isroil [janob Musa Mendelsonga yozgan maktubida yorug'lik va huquqni qidirish" Mannaseh Ben Isroilga kirish so'zi] ", Altmann, Aleksandrda; Bamberger, Fritz (tahr.), Musa Mendelson: Gesammelte Shriften - Jubiläumsausgabe, 8, Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog, 73-87 betlar, ISBN 3-7728-0318-0.

- Dohm, Kristian Konrad Vilgelm fon (1781–1783), Ueber die bürgerliche Verbesserung der Juden, Erster Theil, Zweyter Theil, Berlin, Stettin: Fridrix Nikolay, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Geyn, Geynrix (1988), "Lutezia. Bearbeitet von Volkmar Hansen", Vindfurda, Manfred (tahr.), Historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe der Werke, 13/1, Dyusseldorf: Hoffmann und Campe, ISBN 3-455-03014-9, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Jakobi, Fridrix Geynrix (1786), Kengroq Mendelssohns Beschuldigungen vafot etadi Briefe über vafot etadi Lehre des Spinoza, Leypsig: Goeschen, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Jakobi, Fridrix Geynrix (1789), Ueber Lehre des Spinoza va Shorten an den Herrn Moses Mendelssohn-da vafot etadi, Breslau: G. Lyov, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Jeykobson, Isroil (1810), Hebräische und Deutsche Gesänge zur Andacht und Erbauung, zunächst für die neuen Schulen der Israelitischen Jugend von Westphalen, Kassel.

- Lavater, Yoxann Kaspar (1774), Herrn Karl Bonnets, akademien Mitglieds, falsafiy Untersuchung der Beweise für das Christenthum: Samt desselben Ideen von der künftigen Glückseligkeit des Menschen. Nebst dessen Zueignungsschrift and Moses Mendelssohn, and und daher entstandenen sämtlichen Streitschriften zwischen Hrn. Lavater, Moses Mendelssohn und Hrn. Doktor Kölbele; wie auch de erstren gehaltenen Rede bey der Taufe zweyer Israeliten, Frankfurt am Mayn: Bayrhoffer, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Marks, Karl (1844), "Zur Judenfrage", Ruge shahrida, Arnold; Marks, Karl (tahrir), Deutsch-Französische Jahrbuxher, 1ste und 2te Lieferung, 182-214-betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

Inglizcha tarjima

- Mendelson, Muso (1838a), Quddus: Ruhiy hokimiyat va yahudiylik to'g'risida risola, tarjima. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 2, London: Longman, Orme, Brown va Longmans, olingan 22 yanvar 2011.

- Mendelson, Muso (1983b), Quddus, yoki, Diniy kuch va yahudiylik to'g'risida, tarjima qiling. Allan Arkush tomonidan, kirish va sharh muallifi Aleksandr Altmann, Hannover (N.H.) va London: Brandeis University Press uchun New England University Press, ISBN 0-87451-264-6.

- Mendelson, Muso (2002), Shmidt, Jeyms (tahr.), Mendelsonning Quddus tarjimasi. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 3 (repr. vol.2 (London 1838) tahr.), Bristol: Thoemmes, ISBN 1-85506-984-9.

- Mendelson, Muso (2002), Shmidt, Jeyms (tahr.), Mendelsonning Quddus bilan bog'liq yozuvlari tarjima qilingan. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 2 (rep. 1-jild (London 1838) tahr.), Bristol: Thoemmes, ISBN 1-85506-984-9.

- Mendelson, Muso (1838b), "Mendelsonning Lavater bilan tortishuvi paytida yozgan maktubi, 1770 yilda", Quddus: Ruhiy hokimiyat va yahudiylik to'g'risida risola, tarjima. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 1, London: Longman, Orme, Brown & Longmans, 147–154-betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1838c), "Musa Mendelsonning Charlz Bonnga javobi", Quddus: Ruhiy hokimiyat va yahudiylik to'g'risida risola, tarjima. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 1, London: Longman, Orme, Brown & Longmans, 155–175 betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Mendelson, Muso (1838d), "" Vindiciae Judaeorum "ning nemis tiliga tarjimasiga kirish so'zi", Quddus: Ruhiy hokimiyat va yahudiylik to'g'risida risola, tarjima. Muso Shomuil tomonidan, 1, London: Longman, Orme, Brown & Longmans, 75–116-betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Dohm, Kristian Konrad Vilgelm fon (1957), Yahudiylarning fuqarolik holatini yaxshilash to'g'risida tarjima qiling. Xelen Lederer tomonidan, Sincinnati (Ogayo shtati): Ibroniy ittifoqi kolleji-yahudiy din instituti.

- (Kranz), (Avgust Fridrix) (1838), "Rabbi Manashe ben Isroilning yahudiylarni oqlashi haqidagi ajoyib so'zboshisi bilan nishonlangan Muso Mendelsonning maktubi - nur va huquqni qidirish", Shomuil, Muso (tahr.), Quddus: cherkov hokimiyati va yahudiylik to'g'risida risola, 1, London: Longman, Orme, Brown & Longmans, 117-145-betlar, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

Tadqiqotlar

- Arendt, Xanna (1951), Totalitarizmning kelib chiqishi (1-nashr), Nyu-York: Harcourt Brace.

- Arendt, Xanna (1957), Rahel Varnhagen. Yahudiy ayolning hayoti, tarjima. tomonidan Richard va Klara Uinston, London: Sharq va G'arbiy kutubxona.

- Baioni, Juliano (1984), Kafka: letteratura ed ebraismo, Torino: G. Einaudi, ISBN 978-88-06-05722-0.

- Berkovitz, Jey R. (1989), 19-asrda Frantsiyada yahudiy shaxsiyatining shakllanishi, Detroyt: Ueyn shtati, ISBN 0-8143-2012-0, olingan 9 sentyabr 2009.

- Blumenberg, Xans (1986), Arbeit am Mythos (4-nashr), Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, ISBN 978-3-518-57515-4.

- Bollaxer, Martin (1969), Der junge Gyote und Spinoza - Studien zur Geschichte des Spinozismus in der Epoche des Sturms and Drangs., Studien zur deutschen Literatur, 18, Tubingen: Nimeyer.

- Kayza, Volker; Eyxler, Klaus-Diter, nashr. (1994), Praxis, Vernunft, Gemeinschaft - Auf der Suche nach einer anderen Vernunft: Helmut Seidel zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet, Vaynxaym: Beltz Athenäum, ISBN 978-3-89547-023-3.

- Delf, Xanna; Shoeps, Yuliy X.; Uolter, Manfred, nashr. (1994), Spinoza in der europäischen Geistesgeschichte, Berlin: Edition Hentrich, ISBN 978-3-89468-113-5.

- O'rmonchi, Vera (2001), Lessing und Moses Mendelssohn: Geschichte einer Freundschaft, Gamburg: Europäische Verlagsanstalt, ISBN 978-3-434-50502-0.